Microplastics Found in Fats and Lungs of Two-Thirds of Studied Marine Mammals, Raising Concerns Over Long-Term Impact

In a recent study conducted by a graduate student at Duke University Marine Lab, researchers have made a disconcerting discovery: microscopic plastic particles have been detected in the fats and lungs of approximately two-thirds of marine mammals examined. This alarming finding sheds light on the pervasive presence of microplastics in our ocean and the potential consequences for marine life.

The study, available to read here as an open access paper, which was led by Greg Merrill Jr., a graduate student at Duke University Marine Lab, involved the analysis of samples collected from 32 stranded or subsistence-harvested marine mammals between 2000 and 2021. These animals, which spanned twelve different species and were sourced from various locations including Alaska, California, and North Carolina, exhibited the concerning presence of polymer particles and fibres embedded in their tissues.

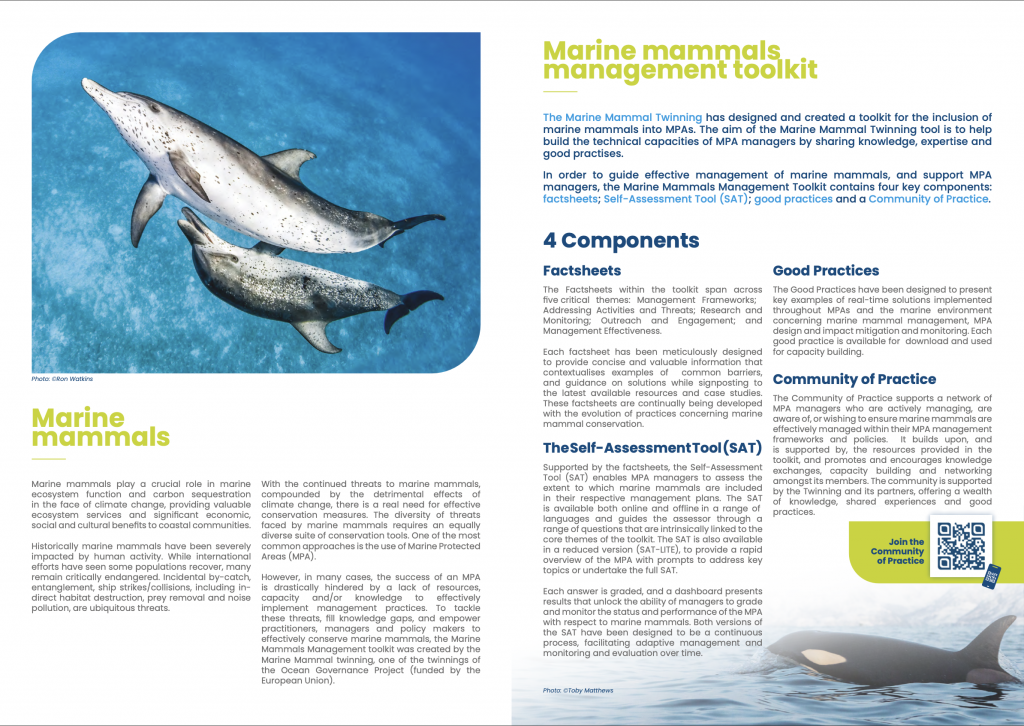

Fig. 1. Figure showing the projections under a scenario of high microplastic concentration to predict the potential bioaccumulation in marine species of the food web. From the bottom to the top: zooplankton, humpback whale, southern resident killer whale, Pacific herring and Chinook salmon. Source: The University of British Columbia

The implications of these findings are significant, suggesting that microplastics are capable of migrating beyond the digestive tract and becoming lodged within the organisms’ tissues. “This is an extra burden on top of everything else they face: climate change, pollution, noise, and now they’re not only ingesting plastic and contending with the big pieces in their stomachs, they’re also being internalised,” says Merrill. “Some proportion of their mass is now plastic.”

The study focused on different tissues, including blubber, the sound-producing melon on a toothed whale’s forehead, fat pads along the lower jaw, and even the lungs. The plastics identified in these tissues ranged in size from 198 to 537 microns, similar in diameter to a human hair. The research team also highlighted the potential physical damage cause by plastic pieces tearing and abrading tissues.

While the exact health implications of these embedded microplastics remain to be determined, the study raised concerns about their potential to act as hormone mimics and the endocrine disruptors. Polyester fibres, commonly found in laundry machines, were the most frequently observed type of microplastic in the tissue samples, followed by polyethylene, a component of beverage containers. Notably, blue plastic was the most prevalent colour detected across all four types of tissue studied.

Merrill emphasizes the broader ecological impact of these findings. Filter-feeding animals like blue whales, estimated to consume substantial amounts of microplastics daily, could be accumulating these particles as they catch tiny organisms in the water column. Predatory marine mammals, such as whales and dolphins that prey on larger organisms, may also be inadvertently ingesting accumulated plastic from their prey.

This study underscores the ubiquity of ocean plastics and the pressing need to address the scope of this problem. While some microplastics are likely expelled through defecation, a concerning portion ends up accumulating in the tissues of marine mammals, potentially affecting their long-term health and wellbeing. “For me, this just underscores the ubiquity of ocean plastics and the scale of this problem. Some of these samples date back to 2001. Like, this has been happening for at least 20 years’” Merrill states.

The research, published in the Journal Environmental Pollution, was supported by funding from the National Science Foundation, the North Carolina Wildlife Federation, and North Carolina Sea Grant. As awareness of the profound impact of microplastics on marine life continues to grow, further research and action are essential to mitigate the ongoing damage to our oceans and the at-risk creatures that call them home.

Read more about Microplastics on the NOAA website.